Though he had spent the previous yr at an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence within the south of France, Vincent van Gogh arrived within the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, just north of Paris, in an optimistic mood. It was here, in 1890, that he would spend the previous few months of his life which, despite the depression that may soon return, were his most efficient.

The move offered him the prospect of a fresh start, near his brother Theo, and under the watchful eye of Paul Gachet, a homeopathic doctor with an interest in art and mental wellbeing. Over the course of the subsequent two months, Van Gogh produced no fewer than 74 paintings and greater than 50 drawings, that are catalogued chronologically by Nienke Bakker, Emmanuel Coquery, Louis van Tilborgh and Teio Meedendorf of their book, Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise: His Final Months.

Ian Dagnall / Alamy

As Van Tilborgh observes within the opening essay, Van Gogh’s final works have “a special, almost existential significance” for us. The paintings most closely identified together with his final days include the profoundly melancholic Wheatfield with Crows (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), whose central path leads us through the golden wheat towards an intensely brooding sky. It was here, within the fields above Auvers, that Van Gogh would shoot himself on the age of 37 in July 1890.

As Meedendorf recounts, Van Gogh was initially enchanted by this “distinctive and picturesque” village nestling in the guts of the countryside. Accessible from Paris by train, it remained surprisingly unspoiled, with thatched whitewashed cottages and a particular medieval church.

At home in nature

Unlike previous inhabitants of Auvers, akin to the landscape artist and precursor of impressionism, Charles-François DaubignyVan Gogh ignored the nearby river Oise. He preferred to record the village, its quaint old buildings merging organically with the landscape and the encompassing vineyards. He also selected surprisingly modern motifs akin to the town hall bedecked with flags and bunting on Bastille Day.

Another essential subject, explored by Nienke Bakker, was a series of floral still lifes, painted between late May and mid-June 1890. Van Gogh had painted irises and roses as if “in a frenzy” towards the tip of his stay at Saint-Rémy and was optimistic that his pictures would discover a buyer, despite the incontrovertible fact that that they had didn’t achieve this prior to now.

He had a preference for wild cornflowers, daisies, poppies, buttercups and thistles, but in addition painted Chinese asters, carnations and marigolds, blossoming chestnuts and acacia, rendered in rhythmic patterns that dominated the image space.

Peter Horse / Alamy

Flowers and ears of wheat appear also in his portraits, most memorably within the two of Dr Gachet, leaning on his elbow in a classic melancholic pose and clutching a sprig of foxglove, which he utilized in his homeopathic remedies.

Gachet was a very important early supporter, not only of Van Gogh, but of the impressionist artists Camille Pissarrowho lived at nearby Pontoise, and Paul Cézannewho painted Gachet’s distinctive white house at Auvers.

The final days

The book features a useful map of Auvers-sur-Oise which identifies most of the sites at which Van Gogh arrange his easel. One of those is Tree Roots(Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), recently identified as the ultimate work produced by the artist.

It is one in every of a series of 13 works that were distinctive for his or her double-square format. As Emmanuel Coquery explains, the format derived from Daubigny, who’s referenced within the third canvas within the series, Daubigny’s Garden (Rudolf Staechelin Collection).

Daubigny continues to be celebrated today within the village. His house and studio, decorated by his friend Camille Corot, and in addition his children, have been preserved for posterity. So, too, has the room on the Auberge Ravoux, wherein Van Gogh died on 29 July 1890.

Fittingly, the last two essays on this brilliantly researched and colourfully illustrated book concentrate on Van Gogh’s final days. Following a visit to Theo in early July, the artist was beset by an prolonged period of depression, brought on by feelings that he was becoming a burden to his brother.

dec925 / Alamy

In his letters he wrote: “My life … is attacked on the very root, my step is also faltering.” He described his latest landscapes as expressions of “sadness, extreme loneliness”. Eventually he shot himself within the chest with a revolver and died in Theo’s arms nearly two days later.

His body was laid to rest in a spacious, sunny plot within the graveyard, near the wheatfields he loved a lot. In 1914, Theo’s stays were transferred to the identical ivy-covered grave, remarkable for its simplicity.

As the ultimate essay by Bregje Gerritse and Sara Tas shows, even before his death, Van Gogh was starting to be appreciated by critics akin to Gustave Kahn and Albert Aurier.

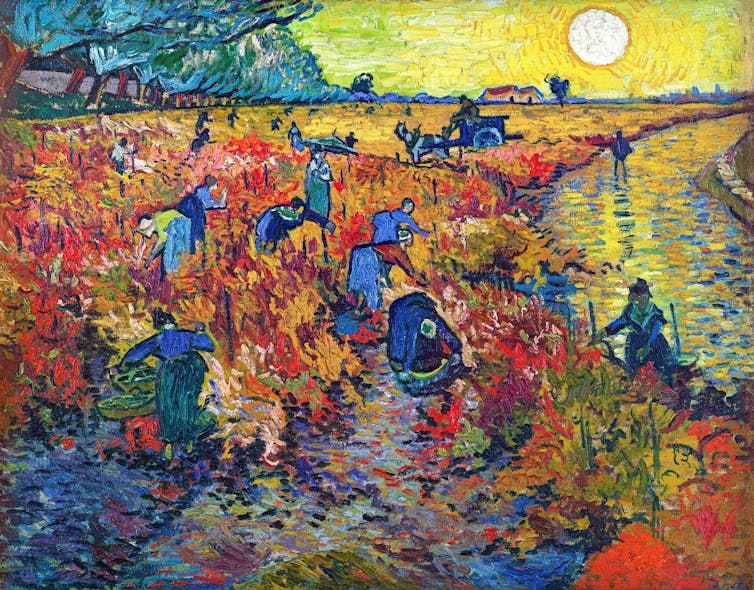

He made his only recorded sale when the Belgian artist Anna Boch purchased The Red Vineyard (Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow) for 400 francs. Before long he would posthumously achieve the celebrity and business success he had so longed for.