In 2011, pop music scholar Simon Reynolds was already observing popular culture’s fascination with its own past, noting that “we live in a pop age gone loco for retro and crazy for commemoration.”

For Reynolds, this obsession with the past has the potential to bring concerning the end of pop music culture: “Could or not it’s,” he asks, “that the best danger to the long run of our music culture is … its past?”

The situation has not improved within the years since Reynolds voiced his concerns. Our fixation on the favored music of previous a long time threatens our future by stifling originality.

Thanks to recording technology, and now to more moderen developments in artificial intelligence and machine learning, we discover ourselves an increasing number of in a spectral present, thoroughly haunted by the ghosts of pop music’s past.

Ghostly presence

This form of hauntedness can provoke anxiety. Hauntology, a theoretical concept originating within the work of French philosopher Jacques Derrida, was later applied to musicology by critic Mark Fisher. Hauntology is worried with memory, nostalgia and the character of being. The present isn’t simply “present,” and the remnants of our cultural past all the time linger or return.

A ghost, in literature, folklore and popular culture, is a presence from the past of something or someone that now not stays. Is a ghost, then, from the past or of the current? As hauntology would insist, a ghost is paradoxically each at the identical time.

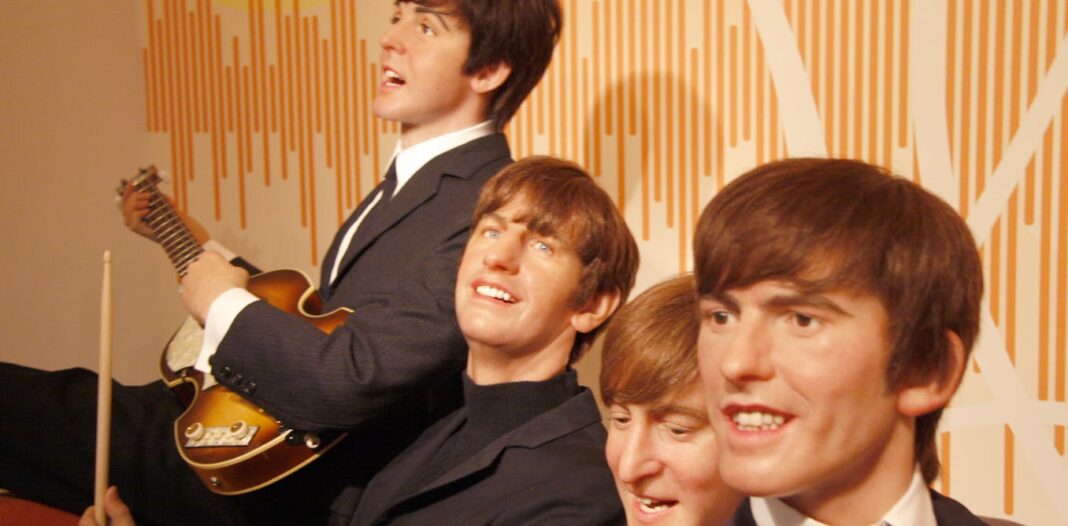

In November 2023, pop phenomenon the Beatles released a “recent” song titled “Now and Then.” It received a rapturous reception from fans and critics alike, and was soon topping the charts within the United States and the United Kingdom, becoming the fastest-selling single of 2023.

The song includes a lead vocal track by the late John Lennon, salvaged from a demo recording he made at home within the late Nineteen Seventies, just a couple of years before his murder in 1980. It also includes archival guitar tracks from the late George Harrison.

The two surviving Beatles, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, contributed recent bass, drum, vocal and guitar parts (McCartney even played a slide guitar solo mimicking Harrison’s sound and magnificence), and producer Giles Martin (son of legendary Beatles’ producer George Martin) provided a string arrangement and a tapestry of background vocals lifted from other iconic Beatles songs.

“Now and Then” was also celebrated for the technological sophistication of its production, and specifically for its use of artificial intelligence. Using software that might tell the difference between a human voice and other sounds on a recording, Lennon’s voice was isolated and reanimated, allowing McCartney and Starr to perform alongside their long-deceased bandmate.

Final masterpiece

“Now and Then,” along with being a “recent” Beatles tune, is probably going also the group’s last: there are not any more old recordings to resurrect, and McCartney and Starr are each octogenarians.

Indeed, in response to music critics like ’s Alexis Petridis, “Now and Then” is an emotionally satisfying “act of closure.” It stands by itself as a real addition to the Beatles’ catalogue, wrapping up the band’s profession and “never stoops to deploying obviously Beatles-y signifiers.”

Music journalist Jem Aswad, writing in , characterizes “Now and Then” as a “bittersweet finale.” While Aswad is mildly critical of the song as an “incomplete sketch,” he insists at the identical time that any further criticism is just unwarranted sour grapes, concluding that it’s “an unexpected pleasure that marks the completion of the group’s last little bit of unfinished business.”

Haunted, ghostly

Some critics, nonetheless, echoing Reynolds’s concerns, found “Now and Then” decidedly less praiseworthy. Josiah Gogarty’s brutal review, published in , argues that the song serves as “an indication of our cultural doom loop,” and likened it to a “séance, calling forth the warbling and the jangling of the dead.”

The recording includes McCartney’s count-in at first and a few studio chatter from Starr at the tip, as if to reassure listeners that the song is a product of living musicians.

At the identical time, the song is eerily placeless or ahistorical, caught somewhere between past and present: a haunted, ghostly thing, evidence of a popular culture that has long ceased to evolve.

Limiting the long run

The problem is the best way songs like “Now and Then” are imbued with nostalgia: they threaten the long run and limit the potential of the emergence of latest ideas.

Fisher feared the effect of this form of nostalgia giving rise to “a cancelled future.” We can readily imagine such a future, because we already inhabit it: a way forward for never-ending tours by impossibly decrepit rock bands, countless re-boots of old movies and tv shows, the fetishization of all that’s vintage.

Even probably the most stunningly progressive technological developments — similar to the AI that made “Now and Then” possible — seems to serve a regressive purpose, namely to resurrect the Beatles.

A generous tackle “Now and Then” could be to view its arrangement and production as capturing and amplifying the meaning of the song lyrics: “Now after which I miss you … I need you to return to me.” These lyrics suggest the presence and absence theorized by hauntology, which is cleverly reflected within the song’s haunted soundscape.

Less generously, “Now and Then,” somewhat than an act of closure, simply continues an ongoing trend of looking backwards in pop music. It indicates that our insecurities about our future ensure we are going to remain ceaselessly entangled with its ghosts.