A person is charged with stealing a really distinctive blue diamond. The man claims never to have seen the diamond before. An expert known as to testify whether the brain responses exhibited by this man indicate he has seen the diamond before. The query is – should this information be utilized in court?

Courts are reluctant to confess evidence where there may be considerable debate over the interpretation of scientific findings. But a recent study from researchers within the US has noted that the accuracy of such “mind reading” technology is improving.

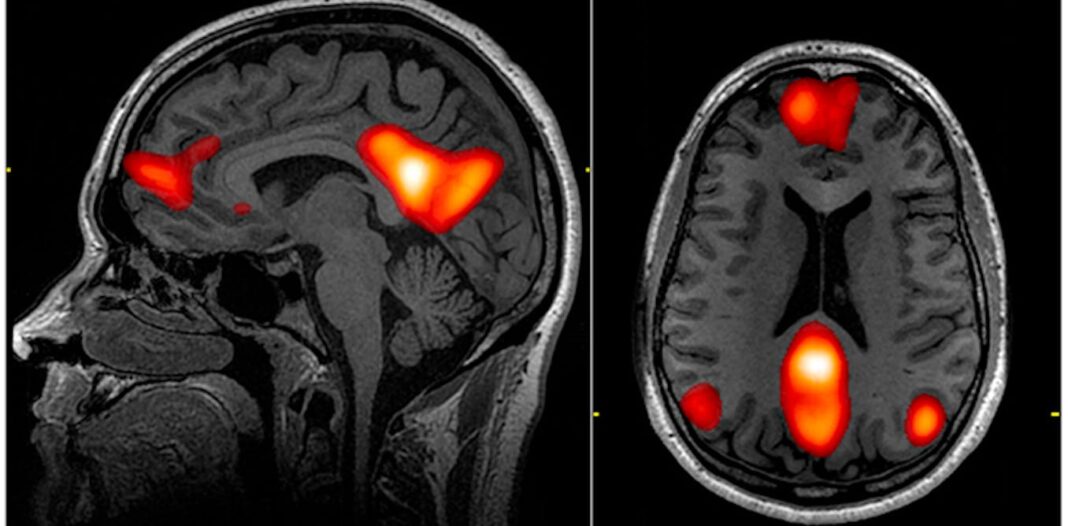

There are various methods of detecting false statements or concealed knowledge, which vary greatly. For example, traditional “lie detection” relies on measuring physiological reactions resembling heart rate, blood pressure, pupil dilation and skin sweat response to direct questions, resembling “did you kill your wife?” Alternatively, a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) approach uses brain scans to discover a brain signature for lying.

However, the technology considered by the US researchers, referred to as “brain fingerprinting”, “guilty knowledge tests” or “concealed information tests”, differs from standard lie detection since it claims to disclose the fingerprint of information stored within the brain. For example, within the case of the hypothetical blue diamond, knowledge of what style of diamond was stolen, where it was stolen, and what style of tools were used to effect the theft.

This technique gathers electrical signals throughout the brain through the scalp by electroencephalography (EEG), signals which indicate brain responses. Known because the P300 signalthose responses to questions or visual stimuli are assessed for signs that the person recognises certain pieces of data. The process includes some questions which can be neutral in content and used as controls, while others probe for knowledge of facts related to the offence.

The P300 response typically occurs some 300 to 800 milliseconds after the stimulus, and it is claimed that those tested will react to the stimulus before they can conceal their response. If the probes sufficiently narrow the main focus to knowledge that only the perpetrator of the crime could possess, then the test is claimed to be “accurate” in revealing this concealed knowledge. Proponents of using this technology argue that this provides much stronger evidence than is feasible to get through human assessment.

Assuming this technology is perhaps able to showing that somebody has hidden knowledge of events relevant to against the law, should we be concerned about its use?

ESB Professional/Shutterstock

Potential for prejudice

Evidence of this kind has not yet been accepted by the English courts, and possibly never will probably be. But similar evidence has been admitted in other jurisdictions, including India.

In the Indian case of Aditi Sharma the court heard evidence that her brain responses implicated her in her former fiancé’s murder. After investigators read statements related and unrelated to the offence, they claimed her responses indicated experiential knowledge of planning to poison him with arsenic, and of shopping for arsenic with which to perform the murder. The case generated much discussion, and while she was initially convicted, this was later overturned.

However, the Indian Supreme Court has not ruled out the potential of such evidence getting used if the person being tested freely consents. We shouldn’t forget that individuals may knowingly conceal knowledge of facts relevant to against the law for all types of reasons, resembling protecting other people or hiding illicit relationships. These reasons for hiding knowledge may don’t have anything to do with the crime. You could have knowledge relevant to against the law but be totally innocent of that crime. The test is for knowledge, not for guilt.

Studio_G/Shutterstock

Context is essential

The US researchers checked out whether brain-based evidence might unduly influence juries and prejudice the fair end result of trials. They found concerns that neuroscientific evidence may adversely influence trials might be overstated. In their experiment, mock jurors were influenced by the existence of brain based evidence, whether it indicated guilty knowledge or the absence of it. But the strength of other evidence resembling motive or opportunity weighed more heavily within the hypothetical jurors’ minds.

This just isn’t surprising, as our case-based research demonstrates the importance of the context during which neuroscientific evidence is introduced in court. It could help support a case, however the success depends on the strength of all of the evidence combined. In no case was using neuroscientific evidence alone determinative of the end result, though in several it was highly significant.

Memory detection technologies are improving, but even in the event that they are “accurate” (nonetheless we decide to define that term) it doesn’t mechanically mean they are going to or needs to be allowed in court. Society, legislators and the courts are going to have to make a decision whether our memories needs to be allowed to stay private or whether the needs of justice trump privacy considerations. Our innermost thoughts have at all times been viewed as private; are we able to give up them to law enforcement agencies?