As a child, I found a small, brown suitcase in my wardrobe. It had two silver latches and a squeaky wooden handle. I didn’t recognise the name inscribed on the bottom in pencil: .

I asked my mother, “Whose suitcase is this?” Mum replied, “Your grandmother’s.”

I was confused about who my grandmother was. Born in the early sixties, I grew up with my parents and two older brothers in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs. Dad had grown up without his mother and was cared for by his paternal grandmother.

It was around the time of my birth when Dad accidentally discovered the secret of his mother’s whereabouts. Ada was living in a mental institution.

As a young child, I remember waiting with my family for Ada in the foyer of a boarding house in Melbourne. This memory is like a single snapshot of a dimly lit, wood-panelled foyer, marked by the tension of my two brothers being scolded for their noisy behaviour as we waited for Ada to join us for a family outing.

Another time, I recall Ada sitting in the lounge room of our family home, smoking cigarettes. I tried to engage her, but she would not smile, and her face and eyes lacked expression. I knew there had been something wrong with Ada. I am uncertain when I learned she had been removed from her children and locked away.

As my father grew to know her more, stories of her absence from his childhood emerged. It was impossible for me as a child to understand Dad was getting to know his mother for the first time as an adult: a parent with his own children.

For a long time, I had the sense Ada had problems related to her menstrual cycle and that once a month, her periods threw her off balance, and she was placed in the sick ward of the mental hospital for one week out of every month.

The notion that being female caused her sickness gave me some foreboding as a young girl. But of course, that wasn’t true: it was just one example of the lies we were told about what had happened to her.

A hidden mother, revealed

Dad had been raised from a baby by his paternal grandmother (a widow), who he knew as Gran. His older sister, Hannah, was placed, aged four, into a Melbourne boarding school for girls, Lowther Hall in Essendon. Dad’s father, who lived elsewhere in the same town, visited the children on Sundays at Gran’s.

The children were reunited when Hannah returned to Gran’s care, aged eight, when Lowther Hall was requisitioned for American military requirements in 1942. Dad grew up assuming his mother was no longer alive.

Dad married my mother in his early twenties. Together, they lived with Dad’s father, who I called Pop. Soon after, Dad and Mum built a new home in the outer suburbs of Melbourne and notified the local post office about their change of address. Dad received a birthday card redirected from his former address. It was signed .

He thought it must have been a mistake. Dad drove to his father’s house, determined to get to the bottom of the situation. He waited a few hours, his mind swirling, before Pop returned home. Finally, he questioned Pop about the card.

Pop admitted it was a genuine birthday card from Dad’s mother: Ada had been living in a mental institution all this time. Pop then produced a bundle of letters and cards Ada had written to her children over more than 20 years. Pop was instrumental in keeping Ada a secret from her children.

Suzy Hazelwood/Pexels

Now, the secret was out: Ada was alive and living in a Melbourne mental hospital. It is difficult to understand why Pop had kept Ada’s letters all this time without saying anything. One can only guess he had intercepted and confiscated Ada’s letters to her children to protect them from the shame and stigma of mental illness.

It seems likely Pop intended to continue Ada’s long estrangement, had that birthday card not slipped into Dad’s hands that day.

Over 20 years of letters and cards, and not one reply. Ada never forgot her children.

The first of many visits

Soon after finding that fateful card, Dad contacted the mental hospital – and met his mother for the first time he could remember. He recalled his first meeting with Ada in the early 1960s at Mont Park mental hospital in Bundoora, Melbourne. He waited to meet Ada in a small walled garden and was told she would not be much longer.

I was nervous and unsure of what she would look like and what to say to her. I waited for 20 long minutes, and my anxiety increased. When she opened the door, there she was. But six people followed her to take a look at her son. I didn’t know whether to give her a kiss or give her a hug. The first thing she said to me was: “You look just like your father.” They were the last words I wanted to hear at that moment.

As Pop had hidden his mother from him, Ada’s comment had a painful sting. This was the first of many visits together. Dad recalled taking us to collect Ada from Carmel House, where I remembered waiting in the foyer for her. We took her on outings and occasional weekends to our family home. He recalled:

When we went to pick her up from Carmel House, she was always late and I remember waiting in that timber-panelled foyer, looking searchingly at the stairs, until she made her entrance. When I was working in the city, Mum used to go and get her hair done on her days off, and we would meet afterwards at the Town Hall corner, and go off to Coles Cafeteria, her favourite eating place. But then she would go into the toilets and wash her hair out, so sometimes when I met her, she looked a bit wild and woolly, like she had been diving in the Yarra River. She certainly had her eccentricities.

As Dad and Ada got to know each other and tentatively forged their new relationship, it was still unclear why Ada was committed to a mental institution in the first place.

Dad and his older sister Hannah had little contact or knowledge of Ada’s family of origin. They were surrounded by the silence of his mother’s whereabouts throughout their upbringing, until Ada’s card arrived for him in his twenties.

‘I felt closer to Ada’

Dad and I wanted to understand the events that precipitated her committal. We found we could access Ada’s mental-patient files by applying for a Freedom of Information request. We discussed it together, and Dad agreed as Ada’s next-of-kin. I purchased Ada’s birth and wedding certificates, to make sure I requested the correct person’s files.

I found out Ada was the younger sister of five brothers. She married in 1934 at 21 years old, and her occupation was stated on her marriage certificate as a “comptometer operator”. A comptometer is a key-driven mechanical calculator, which was operated predominantly by women, and her occupation suggests Ada had completed a specialised business course. Advances in office technology in the early 1930s gave many young and unmarried women like Ada new opportunities for employment in clerical positions.

However, most industries excluded married women, and it’s likely Ada left her job when she married my grandfather in 1934, and moved to the country.

Three months after making the request, we received Ada’s mental-patient files, which ranged from her original committal in 1936 to her death in 1972. Ada’s records include the committal certificates, diagnoses, notes on trial leave, experimental treatments, and her final years as an outpatient at Carmel House.

As I opened the files for the first time, Ada’s headshot appeared on the first page of her first admission certificate in 1936. Her shoulders are angled and her gaze is focused to the right of the camera’s lens.

At age 24, Ada is youthful and smiling. She wears a dress with a large, white collar, possibly the same clothes she wore when she left home. I was shocked to see our similar physical appearance. I could see my face in hers: the same high forehead, small eyes, fair skin and wavy hair. I felt closer to Ada.

Ada’s patient files show her mental health began to deteriorate following the birth of her second child. She experienced auditory hallucinations when committed to the Royal Park Receiving House in Melbourne in 1936, two weeks after giving birth. The doctor described her as lucid, with “nervous symptoms that alternate between depression and exaltation along with auditory hallucinations”.

‘Puerperal insanity’ – associated with giving birth

The cause of her attack is noted as “puerperal insanity”, which psychiatrists associated with Ada giving birth two weeks before.

Hilary Marland, in her book Dangerous Motherhood, argues puerperal insanity is a 19th-century diagnosis that links insanity to recent childbirth – and links lactation, pregnancy and miscarriage to mental illness. Marland found that in the 19th century, puerperal insanity accounted for approximately 10% of admissions in English asylums.

I found a similar rate of birth-related committals had occurred in Victoria in the early 20th century, in my PhD thesis Maternal Insanity in Victoria, Australia 1920-1973.

Alexander Wallis’ article Unnatural Womanhood suggests puerperal insanity, in today’s terms, is understood as postnatal depression.

Four days following Ada’s first admission, her doctor recorded his observations:

The patient is cheerful and talkative. She says that lately, she has had numerous auditory and visual hallucinations. She is quite disorientated as regards time and place. Her answers to questions are quite irrelevant and she smiles and talks cheerfully most of the time.

I researched the history of “puerperal insanity” and its association with dangerous mothers and infanticide. A dark and taboo subject, it conjures the “madwoman” trope in our cultural imagination and is rooted in popular discourses of the murderous mother, the crazy wife in the attic, or the suicidal mother.

The horror of maternal insanity plays on our worst fears: as vulnerable young babies, we depend on our mothers to care for us.

It’s upsetting that an outdated 19th-century diagnosis was still being used to commit mothers like Ada in 1936. In the 100 years that had passed since “puerperal insanity” was coined, psychiatry had still not developed a better understanding of motherhood, or mental illness.

Within the first two months of her committal, the doctor described Ada as “restless, apathetic, and erratic in behaviour”. The timing of giving birth and the changes in Ada’s behaviour led to the diagnosis of “puerperal insanity” and her committal in 1936.

Yet her files lack information on the length of her labour, delivery method and the health of the mother or the newborn child. Unfortunately, Ada had given birth at a time in Victoria when mothers faced severe health risks during childbirth, due to poor standards in obstetrics.

A difficult or protracted delivery may have contributed to Ada’s deteriorating mental health, but the details of birth events are rarely included in a mother’s mental files. Despite the lack of information on Ada’s birth experience, her psychiatrists continued to tie childbirth with maternal insanity, as they had in the past.

Nine months after her original committal, Ada went home on trial leave. By March 1938, she was fully discharged as recovered. Ada spent the next two years at home with her family. Then, she became pregnant with her third child.

Unfortunately, Ada’s behaviour became erratic during pregnancy. With consent from her husband, she underwent a “therapeutic abortion” and sterilisation.

I found these procedures a disturbing part of Ada’s files. Her history of puerperal insanity likely provided the psychiatric grounds to proceed, but it did not bring her peace of mind.

In May 1940, soon after the therapeutic abortion and sterilisation, Ada was re-committed back into a mental institution, this time to Mont Park Hospital for the Insane in Melbourne – where she was when Dad found her in the early 1960s.

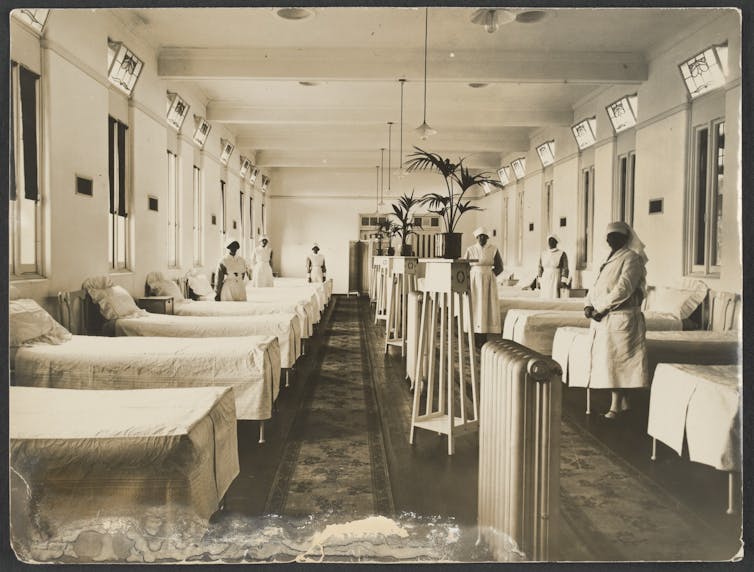

State Library Victoria

‘A world divorced from reality’

Ada underwent a series of insulin-coma treatments (ICT) for the next three months. ICT involves giving patients daily injections of insulin to induce hypoglycemia and coma. Manfred Sakel developed ICT in Europe and at Mont Park the therapy was implemented by Dr Farran-Ridge and Dr Reynolds.

Under the supervision of Dr Reynolds, Ada showed “marked improvement” following ICT every morning for three months:

Mentally much improved – states she is no longer hallucinatory although remembers that she was so and seemed to have gained full insight into her condition. A satisfactory remission.

ICT appeared to aid Ada’s recovery by ending her auditory hallucinations for the first time, but these effects did not last. It proved a dangerous and experimental treatment when some patients died due to complications. Ada experienced a short-lived remission and again returned home for six months of trial leave.

Wikipedia

Upon her return to the institution, Ada suffered grandiose delusions. It is hard not to believe going home on trial leave, considered helpful in some instances, contributed to Ada’s worsening mental health. Her doctor described her delusions of grandeur in January 1942:

She claims she arranged the introductions between Duke & Duchess of Kent. She is willing to oblige for a fee of 1000 pounds to do same for the royal personages. She stated this country is now known as L’Aurolia Republic – it was Australia prior to the revolution in 1900. She says she is a member of Russian Royal family and her real name is Lily Vertel Rose Alvaradora Icebel and says herself “Alvara Russia”.

She has numerous other fantastic and bizarre delusions. Naturally she is somewhat exalted. She admits hearing voices talking about British Secret Service work so cannot divulge subjects discussed. She is cheerful and cooperative, her mood is cheerful, but she is living in a world divorced from reality.

Dad and I marvelled at Ada’s audacity, intellect, and creativity in her grandiose delusions as a Russian princess and British spy. We wondered if our royal status had gone awry.

Further examples of her grandiose delusions are evident in two letters Ada wrote and held within her files. The first letter is Ada’s application to join the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Services in 1943. It is her response to a recruitment drive that sought women to help with increased naval demands. She offered her medical services as a trained doctor and surgeon, fabricated her educational credentials and persisted in her claim of royal birth.

The hospital surveilled all patient letters and prevented Ada’s application from being sent. The address she provided for correspondence was the Female Ward, Mont Park Mental Hospital, which indicates Ada had some grasp on her present reality.

Like the other thousand women who enlisted with the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Services by the end of 1942, Ada wanted to help in war service and gain employment.

The second letter in her files, written in 1943, is addressed to her husband. It reads in part:

One of the patients here has been friendly and helps to pass the time. With your consent, we are planning to go to England together as I must see to my English affairs, being of Russian titled birth. I inherited from my father about twenty-six years ago, various properties in England, America and Australia, also Europe, these properties, and affairs await my attention in London. Also my Army Commission, with the British Secret Service, which commission continues from my last visit to London.

And lastly, my enormous will, I must change it to include yourself, my husband, and only two children, and those several titles to descend upon both, also a ducal title upon yourself from marriage (to me), now Alva.

Ada certainly did not see herself as any ordinary mental patient. Instead, her grandiose delusions illustrate her desire for social mobility and increased status – by casting herself as a wealthy Russian royal working as a British spy. Such grand ideas likely provided Ada with a sense of purpose, power and optimism.

In Victoria Shepherd’s book, A History of Delusions: The Glass King, a Substitute Husband, and a Walking Corpse, the author argues delusions are a far preferable alternative to the dramatic loss of status that occurs when a life goes catastrophically wrong. Delusions serve to reconcile a fallen and lowly existence.

We can see this in Ada’s grand delusions: acting as royalty and a highly educated spy gave her ambitions direction and a sense of purpose, as a patriotic Australian and loyal subject to the British Crown and the Commonwealth during wartime. The Women’s Royal Australian Naval Services application attests to this. Shepherd also reminds us that by listening very closely, we can gain a deeper understanding of people experiencing delusions.

I hear Ada’s demand for dignity and respect as her response to the injustice she suffered – and to the loss of her autonomy, power, freedom and the ability to mother her two children. Unfortunately for Ada, displaying her grand delusions meant no further trial leave, following her return to Mont Park in 1943.

A schizophrenia diagnosis

Ada spent the next 20 years in several mental institutions in Victoria without trial leave, which was often a pathway to discharge for patients with supportive families. Her files are brief throughout the rest of the 1940s and mid-1950s, following Ada’s grandiose delusion letters.

In 1948, her doctor noted Ada was “considerably improved, is much quieter, works in the wards and is no trouble in any way”. A further entry states she is a “delusional schizophrenic whose moods are variable”.

This is the first time “schizophrenic” has been used in Ada’s files. By 1954, Ada is transferred from B ward to A ward. She:

works daily in B ward, which she calls going to the office. Some delusions. Wishes to go home and finish her studies at the university.

The mention of her ward work as “going to the office” shows her sense of humour and is a reminder of the days she worked in an office, as a comptometer operator, before her marriage.

And her desire to complete university points to her desire for social mobility through educational aspirations.

Domestic service

In the 1950s, Ada worked as a domestic servant for Dr Donnan and his family, when he was a medical officer at Mont Park mental hospital. After one year, Dr. Donnan was promoted to Chief Superintendent Psychiatrist at Beechworth Mental Hospital in regional Victoria, and the family took Ada with them.

Sally, Dr. Donnan’s youngest daughter, recalls travelling with her family and Ada from Melbourne to Beechworth for her father’s new position:

There were five of us, including my elder sister, driving up to Beechworth in Dad’s Alvis vintage car with lots of luggage. It got dark and none of us were that comfortable being in the middle of the bush at night. The car conked out at a river crossing, water was running over the road, in the dark. Ada was sitting between us two kids in the back, gripping our hands. Anyway we got going again, though I don’t remember the rest of the trip.

Ada lived in the Donnan’s family home located within the grounds of the mental hospital and continued to work as their domestic servant. The Beechworth Mental Asylum was built in 1867, and by the 1970s it was renamed Mayday Hills Psychiatric Hospital. It still stands today.

Courtesy of the Bourke Museum, Beechworth Victoria

Sally recalls Ada and her mother working together in their home:

Everything was on time, the routine, brushing hair, cleaning shoes, preparing school uniforms and meals. I seem to remember Ada being dressed very neatly every day, usually in a black skirt and white shirt. She wore her hair in a well-cut bob. I always remember her wearing thick beige stockings and stout black shoes. Pink complexion, blue eyes. She never wore makeup.

By 1963, Dr. Donnan transferred to Brierly Mental Hospital in Warrnambool, Victoria, but this time the Donnan family could not take Ada with them.

Ada transferred back to Mont Park in Melbourne, and in the doctor’s transfer request, he wrote:

She spent all her time working for Dr Donnan. She worked quite satisfactorily and seemed very happy with Dr Donnan and his family. After Dr Donnan left the hospital she is missing the family very much and would like to return to Mont Park.

Late days

It was around this time Dad first met Ada, anxiously waiting for her in that walled garden at Mont Park. In 1964, a year and a half later, Ada moved to Carmel House, a residential boarding house for female patients in Preston, Melbourne. From there, she continued to work as a domestic servant and regularly met my father for lunch at Coles cafeteria in the city.

By this time Ada’s condition was described as a “chronic schizophrenic, with auditory hallucinations, and has delusions that she is related to royalty”.

The antipsychotic drugs Stelazine and Mellaril were prescribed for the first time. Ada’s grandiose beliefs persisted well into the 1960s, as my father recalls:

The first time Mum stayed at our place for the weekend, she turned to me and

said “Tell me, do you still use your title?” “Er, what title’s that, Mum?” I asked, surprised. “Lord …” she replied, as if everyone knew. “No Mum. People don’t use their titles much these days.” “What a pity,” she said and dropped the matter.

Ada lived at Carmel House until she died in 1972, aged 60. When I was 11, I accompanied my father there, shortly after Ada’s death. It seemed forever that I waited for him in the car, the sun burning through the glass.

Dad returned and placed that small, brown suitcase, which would later make its way into my childhood bedroom, on the back seat. It was the total of his mother’s personal effects. “Not much for a life,” he said.