The publication last year of Steven M. Weine’s Best Minds: How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness has reinvigorated enduring questions about the relationship between mental health and creativity. As the title suggests, these questions are at once literary and sociopolitical.

Does mental illness beget great poetry? Many poets – celebrated and obscure, from antiquity to the present – have, to varying degrees, navigated issues of mental health. But does this lead to literary excellence? How do we address such questions, which are themselves not exactly unproblematic?

Leaving aside any evaluation of “greatness” and “excellence” for gatekeepers of canon to squabble over, we need to be wary of the cult of the – the accursed, damned or doomed poet – and particularly the propensity to romanticise, even fetishise, such poets and their work.

Needless to say, there exist long traditions across many cultures of treating “madness” as a conduit of vision, illumination, prophecy. Those deemed “mad” have often been treated as seers, vehicles of a truth which goes against the current of quotidian life, disruptors of the systems of “civilised” society.

Such traditions of lionising outsiders as poet-seers are complicated in post-industrial society. Weine frames “madness” as culturally ascribed, but “mental illness” as clinical. The latter is pathologised according to what Michel Foucault called the “clinical gaze” of society’s institutions. Its definitions are subject to ideological and technocratic shifts in those societies.

An example is the United States at the height of Cold War paranoia and Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist and antiwar movements which were a direct rebuttal to a dehumanising politics. This was a society that pathologised “otherness”. A picture-perfect patriotic citizenry of White, middle-class, heterosexual, family-oriented consumers was the norm. Deviations were viewed with suspicion. They represented a threat to be neutralised or, failing that, contained for the sake of the nation’s “integrity” and security.

Allen Ginsberg called this a “Syndrome of Shutdown”: a “healthy” society was one that, in offering material abundance (to a select citizenry), asked for unquestioning conformity, the denial of body and individual consciousness, experience, language.

American poets such as Ginsberg, Bob Kaufman, Elise Cowen and Wanda Coleman, each of whom experienced mental health issues and confronted those experiences in their art, ruptured these structures. They illuminated the individual human toll of struggling against such a climate of fear and numbness.

In doing so, they exposed the sickness of the society that sought to pathologise and contain them. Each of these four poets expressed, through their own unique poetics, a sensibility encapsulated by novelist Jack Kerouac in Belief & Technique for Modern Prose (1959): “No fear or shame in the dignity of yr own experience, language, and knowledge.”

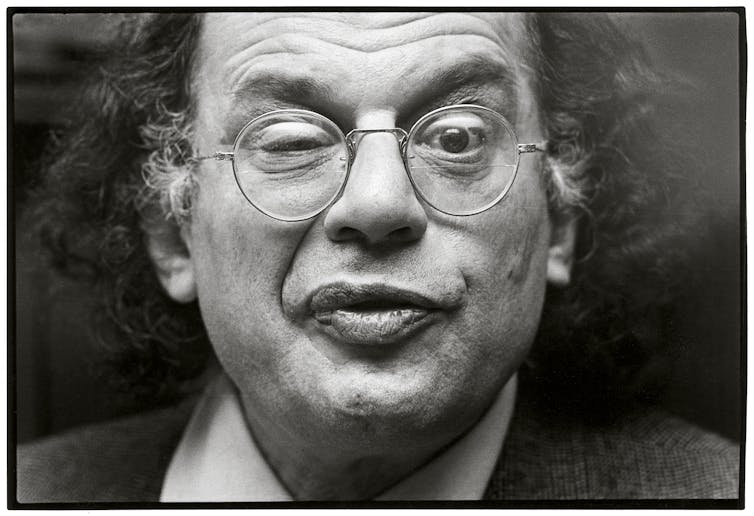

Michiel Hendryckx, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Witness and lament

As a psychiatrist, Weine brings a distinct perspective to Ginsberg’s well-traversed biography. He hits all the major ports, especially those pertaining to the relationship between poetry and Ginsberg’s mutable understanding of “madness”.

From a young age, Ginsberg witnessed the harrowing struggles of his mother Naomi with paranoid schizophrenia. She spent two decades in and out of psychiatric hospitals.

Ginsberg’s own experience at the Psychiatric Institute of the Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, where he was a patient for eight months in 1949, was catalytic. It is where he met Carl Solomon, the dedicatee of Howl, his best-known poem. It also sowed the seeds of a poetics of compassion and healing, which Ginsberg would develop throughout his career.

Howl is a candid, incantatory Jeremiad of witness and lament, and a cry of human compassion and salvation. The opening line, though one of the most overquoted in 20th century American poetry, is not as clear a declaration as it seems:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving, hysterical, naked

Is this “madness” innate in the “best minds”, or is it thrust upon them from without? Is it the destructive madness of society itself?

There is a deliberate ambiguity here, which Ginsberg in part clarifies with the question-and-answer at the beginning of the poem’s second section:

What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imaginations?

Moloch!

The modern metropolis takes on the form of Moloch, the child-devouring pagan god of the Old Testament. It is monstrous, sustained by the sacrifice of innocents.

Moloch whose love is endless oil and stone! Moloch whose soul is electricity and banks! Moloch whose poverty is the specter of genius! Moloch whose fate is a cloud of sexless hydrogen! Moloch whose name is the Mind!

This Mind, synonymous with Moloch, is one conditioned to alienate any human value. It is an abstracted intellect, so severed from the heart and body that it bore the hydrogen bomb. To be out of this Mind, then, may be to retain your humanity. But this makes you a problem for society.

As Weine points out, Ginsberg understood this in terms of the bivalent nature of madness as “either liberatory or damaging”. His exploration of the tension between these perspectives led him to “blow these concepts wide open in his poetry”.

This coincided with the opening up of Ginsberg’s verse to a long Whitmanic speech-based breath: to expansive lines, incantatory repetitions, declarations, reportage, catalogues of images.

It is no coincidence that, in addition to Walt Whitman, Howl was inspired in part by Christopher Smart’s poem Jubilate Agno, which Smart wrote while confined to an asylum for what is now believed to have been manic depression. Ginsberg also drew on Ode to Walt Whitman by Federico Garcia Lorca, who also suffered from depression and anxiety over the discovery of his homosexuality, and the first prelude of At the Top of My Voice by Vladimir Mayakovsky, who committed suicide in 1930.

When Ginsberg insists, in the third part of Howl, that “the soul is innocent and immortal it should never die ungodly in an armed madhouse”, he points to a life beyond the structures that pathologise and contain that which is, in essence, divine and uncontainable.

Ginsberg would refine his poetics in subsequent works, such as Kaddish (1962), a wrenching threnody and loving eulogy for his mother, who died in Pilgrim State Hospital not long before the publication of Howl.

I am not me

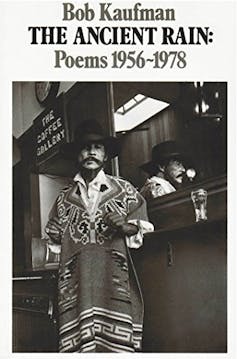

Ginsberg’s countercultural credentials were ratified by the obscenity trial over Howl in San Francisco during the summer of 1957, which brought the “Beat Generation” to national attention. But the Beat poet is Bob Kaufman.

Kaufman was a dextrous and mellifluous jazz poet. He is regarded as a great American Surrealist. The popularity of his poetry in France led to him being dubbed, somewhat fetishistically, “the Black American Rimbaud”. The iconic , Rimbaud famously declared: “The Poet makes himself a visionary through a long, boundless, systematized disorganization of the senses.”

Kaufman fused these influences into an improvisatory, impressionistic, candid poetics. His verse was largely composed on the tongue and recited in the moment, often in public spaces such as cafes and streets. Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, recalled first seeing Kaufman when the poet stuck his face, covered in Band-Aids, through the open windows of tourists’ cars and started “babbling” his poetry.

Such public disruptions by a Black man in segregationist America did not go unnoticed by city authorities. Kaufman was constantly harassed, jailed and even beaten by police. This happened so often that the Co-Existence Bagel Shop, a bohemian hangout where Kaufman was a fixture, kept a collection tin on the counter for his legal costs.

Kaufman endured periods of drug addiction, erratic behaviour and destitution.

His struggles with mental health were in no small part due to the trauma and brutality of his experiences. Following his arrest on the trumped-up charge of walking on the grass during a protest in New York, he was institutionalised and underwent electroshock treatment. Along with head trauma he had received, this caused lasting physical, psychological and spiritual damage.

Kaufman rarely spoke after this. His decade-long vow of silence, beginning in 1963, was less a reaction to John F. Kennedy’s assassination (as is often claimed) than a protest against a dehumanising society that refused to see him.

How does Kaufman’s poetry bear witness to his inner world and the sociopolitical realities he was forced to navigate? His Jail Poems, written in San Francisco City Prison in 1959 – the same year he founded the literary magazine Beatitude with Ginsberg – are in dialogue with Rimbaud’s “” (“I is an other”) and, it could be argued, W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept of the African American’s “double-consciousness”, which arises from the conflict between an individual’s self-identity and the society’s perception of them. In the seventh Jail Poem, he states:

Someone whom I am is no one.

Something I have done is nothing.

Someplace I have been is nowhere.

I am not me.

A psychically and spiritually itinerant Kaufman ends the poem burdened by the very idea that the world sees him as “no one … nothing … nowhere”.

“All these strange streets / I must find cities for,” he writes. “Thank God for beatniks.”

Amen.

Elipse

This sense of an absence, even in presence, of an incapacity or refusal to complete in full a social transaction, make a connection, is evidenced in a different way by Elise Cowen.

Cowen’s life and work are entwined with Ginsberg’s. The two were good friends, romantically involved for a period after Ginsberg’s therapist insisted he enter a heterosexual relationship for the sake of his mental health. Both had met Carl Solomon while institutionalised.

When we compare their poetry, we can see how their aesthetic differences are, in fact, two sides of the same coin. Ginsberg’s lines are expansive, kinetic and declarative. Cowen’s lines are short, economical, textually sparse and restrained, even quiet. Yet at the same time, they are effusive and direct, not unlike the poetry of her greatest literary influence, Emily Dickinson.

Like Whitman and Dickinson during the Civil War era, the work of Ginsberg and Cowen is responding to a society, indeed a nation, in crisis. Their individual sense of themselves – their humanity – easily becomes either consumed in this pervasive malady, or otherwise alienated, displaced and unmoored.

Here, the malady of the sociopolitical and the personal reflect one another, even merge:

Faithful paranoid

It’s all One to you, isn’t it.

Real. That is.

Literal enough

To find a snoozing place among thick visions

Till she’ll stumble over you

With few words and a sense of reluctance, Cowen fans the paranoia in the poem. She makes the reader question who is being paranoid, putting them right in the experience of Cold War paranoia, as well as the experience of someone struggling with it privately.

Words, like individuals, are often ambiguous, unstable, elusive:

I can’t understand who

what I am or anybody else says anymore

the words have no meaning

other than themselves

Even a poem with words that are clear and direct can present a double meaning, as in one of Cowen’s last poems:

No love

No compassion

No intelligence

No beauty

No humility

Twenty-seven years is enough

[…]

Let me out now please –

– Please let me in

Perhaps it is too simplistic to read the final couplet as ambivalence or a duality, even a schism. I have come across literal readings of this poem that treat it as Cowen’s suicide note and the couplet as a harbinger of her demise.

Cowen jumped through a closed window in her parents’ seventh-floor apartment, having checked herself out of Bellevue Hospital, where she was being treated for psychosis. Her journals and poems were destroyed by her parents to erase any evidence of her same-sex relationships and drug use.

What survives of her body of work is, like the poems of Sappho, fragmentary, incomplete. Her writing, kept by friends, was only published as a collection over half a century after her death. Cowen is here and not-here, conspicuous in her absence, inconspicuous in her semi-presence.

Ginsberg’s nickname for her is apt: “Elipse.”

why ain’t you dead

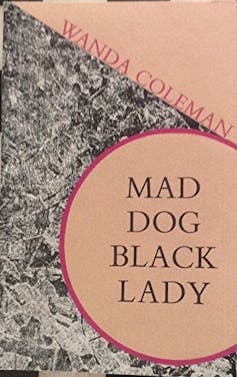

Wanda Coleman, often regarded as the unofficial Poet Laureate of Los Angeles, is a poet of personal and political witness. She is vulnerable, yet uncompromising in her resilience and protest.

Her debut collection, Mad Dog Black Lady (1979), heralded a series of works that laid bare her experiences of day-to-day survival as a Black woman and, for extended periods, a single mother, its horror and humour.

Unlike Ginsberg, Kaufman and Cowen, Coleman was not institutionalised. But she struggled with depression, low self-esteem and body image, and loneliness. She had suicidal thoughts in response to what she often felt was the inescapable hopelessness of her life in America.

She faced the bleak horizons and trauma of institutional racism, sexism and political and economic injustices – realities deeply ingrained in a society which was indeed pathological in its blindness to and even repudiation of her life, her humanity, her dignity and self-worth.

In a nation which believes its own mythology of “liberty and justice for all”, we may at times be awed by the harsh human toll her words expose. Coleman acknowledges the remarkable fact of her simply remaining alive:

i’m sorry i didn’t remember that that that

that that that was so important to youwanda you’re ALWAYS on the attack

wanda wanda wanda i wonder

why ain’t you dead

Robert Frost famously advises that “the only way out is through”. Easy for him to say. Coleman is not allowed to see a way out of her struggles. But she writes through them, showing us how conditions need to change. Her poem The Saturday Afternoon Blues makes this plain in its first lines:

can kill you

can fade your life away

friends are all out shopping

ain’t nobody home

suicide hotline is busy

and here i am on my own …

Coleman said in a late interview: “I believe in the power of creative writing to change, heal, and transform.” Her work was inspired by day-to-day events and people she observes, and the “who, what, when, where, why, and how” of journalism.

Style was the final, important consideration in her writing. She observed that she was “using the vernacular with what I know of figurative language”. No other poet moves and sounds and illuminates like Coleman. We can perhaps argue that herein lies her victory.

Why do we turn to poets such as Ginsberg, Kaufman, Cowen and Coleman? Perhaps it is because, to paraphrase Marx, they wake the world up from its dream about itself.

These literary outlaws – renegades, mavericks, partisans – tell us the truth. Their “authenticity” stands, as they did, outside the systems and institutions that marginalised and pathologised them. They illuminate that which we are unable or unwilling to see in society and in ourselves – and perhaps liberate us, at least momentarily, from our conditioning and self-delusions.

In this, they take us outside ourselves. In their candid and vulnerable, often idiomatic, scatological and spontaneous transmission of consciousness and experiences that are atypical, they teach us empathy and compassion. In a dehumanising society hurtling nihilistically towards its endgame, these poets’ salvation of the human – in its varying sensibilities and vulnerabilities – is indeed revolutionary.