Victor Farra private within the 1st Infantry Battalion, was among the many first to land at Anzac Cove just before dawn on April 25 1915.

© Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia) 2024, CC BY-NC-ND

In the chaos, Farr went missing. When the primary roll call was conducted on April 29, he was nowhere to be found. His record was amended to read “missing”, something guaranteed to send any parent right into a blind panic.

It was not until January 1916 that it was determined Farr had been killed in motion in Turkey sometime between April 25 and 29. He was 20 years old when he died.

His mother, Mary Drummond, had spent months in agony waiting for any news of her only child. Her initial deference to authorities gave approach to an increasingly desperate and offended correspondence. She wrote:

Now Sir, I feel it’s your duty […] when a mother gives her son […] when that son is wounded, she must have some news.

By October, she tried to enlist the assistance of her local member of parliament, imploring him to search out out if her son was alive.

But it was not until 1921, six years after Farr was last seen alive, that the military conceded exhaustive enquiries had did not locate his body. She replied:

I only wish you would tell me if you happen to knew he was buried, my sorrow wouldn’t be so great.

Farr’s name is etched on a panel on the Lone Pine Memorial to the Missing at Gallipoli, together with more than 4,900 of his Australian comrades who likewise don’t have any known grave.

Read more:

How Anzac Day got here to occupy a sacred place in Australians’ hearts

A heavy price

Almost half of the eligible white, male population of Australia volunteered and enlisted within the First Australian Imperial Force between 1914 and 1918.

Of the 416,000 who joined up, greater than 330,000 men served overseas. Of these, greater than 60,000 would never return. These are amongst the best casualty figures for any combatant nation in the whole war.

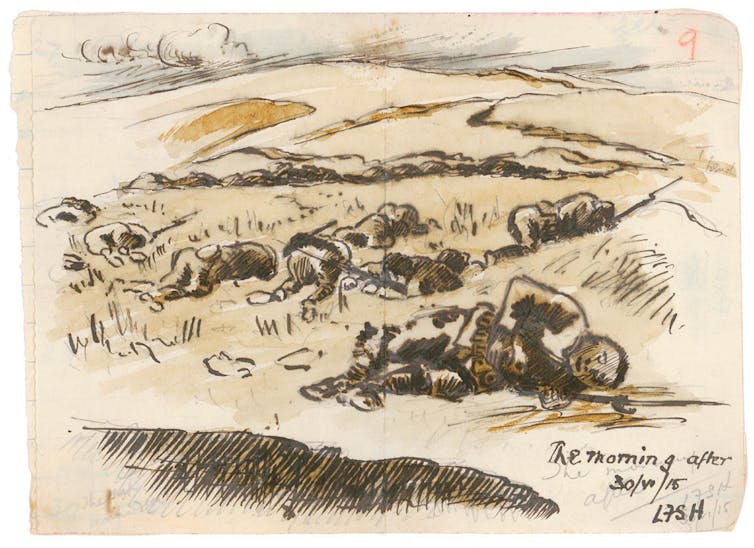

Leslie Hore/Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Over 80% of Australia’s soldiers were single, like Farr; in some rural communities, that rate was about 95%. So the burden of bereavement fell on the shoulders of ageing parents.

The impact of wartime bereavement on ageing parents was enormous. For some, grief became the first motif for the remaining of their days. For most, the memory haunted them into the post-war years, and for all, the war became the pivotal event of their lives, after which nothing would ever be the identical.

Read more:

Women have been neglected by the Anzac tradition, and it is time that modified

Some ended up in mental hospitals

The physical health of many parents declined rapidly once they heard their son had died. One example was Katherine Blair. She died unexpectedly on the age of 54 from heart failure on the primary anniversary of her son’s death in France.

There was evidence of moms and dads becoming violent, enthusiastic about suicide, causing public disturbancesand turning to alcohol of their distress.

As I outlined in my PhD thesismany working class moms and dads joined the wards of public mental hospitals, akin to Callan Park in Sydney. Some stayed there for the remaining of their lives.

Adam.JWC / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The psychiatric files I examined from several major mental hospitals showed evidence of delusions, fantasies and complete denial about their son’s death. Some had lost multiple son.

Upper class families avoided the stigma of public mental hospitals, as they may afford to see private doctors, and have nursing assistance at home.

Upper class fathers, particularly, appointed themselves as guardians of their son’s memory. They spent an inordinate period of time, effort and funds on lobbying the Australian government for recognition of their son’s service, and producing elaborate memory books and commemorative artefacts. Perhaps this was a sign of obsessive griefbut one not available to working class families.

Read more:

Telling the forgotten stories of Indigenous servicemen in the primary world war

How mourning modified

Death and injury throughout the war touched every a part of the country, from cities to hamlets, from towns to stations.

The scale of loss was as shocking because it was unprecedented, and permanently modified the culture of mourning practices in Australia.

Funeral services and overt displays of mourning differed in line with class. Overall, nevertheless, the Australian experience of death within the nineteenth century was based on traditions embraced in Victorian England – deathbed attendance, the graveside funeral service, the headstone and its inscription, and the physical act of visiting the grave to put flowers or other mementos on special occasions.

There was also the practice of wearing mourning black and for wealthier families, ornate funeral processions through the streets with plumed horses to show the social standing and piety of the deceased.

Aussie~mobs/Flickr

However, two realities were required to mourn inside the comfort of those familiar rituals – the knowledge of how and where their loved one had died, and the presence of the body.

Neither was available to the bereaved in Australia throughout the Great War. These established, reliable patterns had been stripped away.

Read more:

Friday essay: images of mourning and the facility of acknowledging grief

Instead, and with so many who were bereaved, the notion of claiming loss in public was seen as tasteless and vulgar.

Rather than funerals being ostentatious public displays, they became private affairs for family and shut friends.

Grief was endured and expressed inside the privacy of the house, with a performance of dignified stoicism in public. The practice of wearing mourning black fell out of fashion.

An estimated 4,000-5,000 war memorials were built across the country. These became the focus for communities to honour their dead and remember their sacrifice, a practice we still see on Anzac Day today.